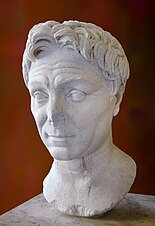

Ptolemy XII Auletes

| Ptolemy XII Auletes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neos Dionysos Theos Philopator Philadelphos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King of the Ptolemaic Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | c. 80–58 BC with Cleopatra V (79–69 BC) c. 55–51 BC (with Cleopatra VII as co-regent 52–51 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ptolemy XI (80 BC) Berenice III (79 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Cleopatra V and Berenice IV (58 BC) Cleopatra VII and Ptolemy XIII (51 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Cleopatra V | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Ptolemy IX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Unknown | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | c. 117 BC Cyprus? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | before 22 March 51 BC Alexandria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ptolemaic dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysus (Ancient Greek: Πτολεμαῖος Νέος Διόνυσος, romanized: Ptolemaios Neos Dionysos, lit. 'Ptolemy the new Dionysus' c. 117 – 51 BC)[nb 1] was a king of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt who ruled from 80 to 58 BC and then again from 55 BC until his death in 51 BC. He was commonly known as Auletes (Αὐλητής, "the Flautist"), referring to his love of playing the flute in Dionysian festivals. A member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, he was a descendant of its founder Ptolemy I, a Macedonian Greek general and companion of Alexander the Great.[note 1]

Ptolemy XII was an illegitimate son of Ptolemy IX by an uncertain mother. In 116 BC, Ptolemy IX became co-regent with his mother, Cleopatra III. However, he was forced into a civil war against his mother and his brother, Ptolemy X, leading to his exile in 107 BC. Cleopatra III sent her grandsons to Kos in 103 BC. They were captured by Mithridates VI of Pontus probably in 88 BC, around the time Ptolemy IX returned to the Egyptian throne. After their father died in 81 BC, Ptolemy XII's half-sister Berenice III took the throne. She was soon murdered by her husband and co-regent, Ptolemy XI, who was then killed. At this point, Ptolemy XII was recalled from Pontus and proclaimed pharaoh, while his brother, also named Ptolemy, was installed as king of Cyprus.

Ptolemy XII married his relative Cleopatra V, who was likely one of his sisters or cousins; they had at least one child together, Berenice IV, and Cleopatra V was likely also the mother of his second daughter, Cleopatra VII. The king's three youngest children – Arsinoe IV, Ptolemy XIII, and Ptolemy XIV – were born to an unknown mother. Ptolemy XII's uncle Ptolemy X had left Egypt to Rome in the event there were no surviving heirs, making Roman annexation of Egypt a possibility. In an effort to prevent this, Ptolemy XII established an alliance with Rome late into his first reign. Rome annexed Cyprus in 58 BC, causing Ptolemy of Cyprus to commit suicide.

Shortly afterwards, Ptolemy XII was deposed by the Egyptian people and fled to Rome, and his eldest daughter, Berenice IV, took the throne. With Roman funding and military assistance, Ptolemy XII recaptured Egypt and had Berenice IV killed in 55 BC. He named his daughter Cleopatra VII as his co-regent in 52 BC. He died the next year and was succeeded by Cleopatra VII and her brother Ptolemy XIII as joint rulers.

Background and early life

[edit]Ptolemy XII was the oldest son of Ptolemy IX. The identity of his mother is uncertain. Ptolemy IX was married twice, to his sister Cleopatra IV from around 119 BC until he was forced to divorce her in 115 BC, and secondly to another sister, Cleopatra Selene, from 115 BC until he abandoned her during his flight from Alexandria in 107 BC. However, Cicero and other ancient sources refer to Ptolemy XII as an illegitimate son; Pompeius Trogus called him a "nothos" (bastard), while Pausanias wrote that Ptolemy IX had no legitimate sons at all.[3][4] Some scholars have therefore proposed that his mother was a concubine – if so, probably an Alexandrian Greek.[5][6][7][8][9] It had been speculated by Werner Huß that Ptolemy XII's mother was an unknown woman belonging to the Egyptian elite, based upon a speculated earlier marriage between Psenptais II, high priest of Ptah, and a certain "Berenice", once argued to possibly be a daughter of Ptolemy VIII.[10][11] However, the speculation of this marriage was refuted by Egyptologist Wendy Cheshire.[12][13][note 2] Chris Bennett argues that Ptolemy XII's mother was Cleopatra IV and that he was considered illegitimate simply because she had never been co-regent.[14] This theory is endorsed by the historian Adrian Goldsworthy.[15]

The date of Ptolemy XII's birth is thus uncertain.[16] If he was the son of Cleopatra IV, he was probably born around 117 BC and followed around a year later by a brother, known as Ptolemy of Cyprus. In 117 BC, Ptolemy IX was governor of Cyprus, but in 116 BC he returned to Alexandria upon the death of his father, Ptolemy VIII. At this point, Ptolemy IX became the junior co-regent of his grandmother Cleopatra II and his mother, Cleopatra III. In 115 BC, his mother forced him to divorce Cleopatra IV, who fled into exile. The former Egyptian queen married the Seleucid king Antiochus IX, but she was murdered by his half-brother and rival Antiochus VIII in 112 BC.[17][18][19] Ptolemy IX meanwhile had been remarried to Cleopatra Selene, with whom he had a daughter, Berenice III.[20] By 109 BC, Ptolemy IX had begun the process of introducing Ptolemy XII to public life. In that year, Ptolemy XII served as the Priest of Alexander and Ptolemaic kings (an office which Ptolemy IX otherwise held himself throughout his reign) and had a festival established in his honour in Cyrene.[21][22] Relations between Ptolemy IX and his mother deteriorated. In 107 BC she forced him to flee Alexandria for Cyprus and replaced him as co-regent with his younger brother, Ptolemy X.[20] Justin mentions that Ptolemy IX left two sons behind when he fled Alexandria.[23] Chris Bennett argues that these sons should be identified as Ptolemy XII and Ptolemy of Cyprus.[14]

Ptolemy IX made an attempt to reclaim the Ptolemaic throne in 103 BC by invading Judaea. At the start of this war, Cleopatra III sent her grandsons to the island of Kos along with her treasure in order to protect them.[24][25] There, Ptolemy XII and Ptolemy of Cyprus seem to have been captured by Mithridates VI of Pontus in 88 BC, at the outbreak of the First Mithridatic War.[22][26] Ironically, their father had reclaimed the Egyptian throne around the same time. They were held by Mithridates as hostages until 80 BC. At some point during this period, probably in 81 or 80 BC, they were engaged to two of Mithridates' daughters, Mithridatis and Nyssa.[27] Meanwhile, Ptolemy IX died in December 81 BC and was succeeded by Berenice III. In April 80 BC, Ptolemy X's son Ptolemy XI was installed as Berenice III's husband and co-regent. He promptly murdered her and was himself killed by an angry Alexandrian mob. The Alexandrians then summoned Ptolemy XII to Egypt to assume the kingship; his brother, also named Ptolemy, became king of Cyprus, where he would reign until 58 BC.[10][28][29]

First reign (80–58 BC)

[edit]

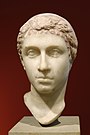

On his arrival in Alexandria, in April 80 BC, Ptolemy XII was proclaimed king. His reign was officially dated as having begun on the death of his father in 81 BC, thereby eliding the reigns of Berenice III and Ptolemy XI. Shortly after his accession, Ptolemy XII married one of his relatives, Cleopatra V.[30] Her parentage is uncertain – modern scholarship often interprets her as a sister,[30] but Christopher Bennett argues that she was a daughter of Ptolemy X.[31] The couple became co-regents and they were incorporated into the Ptolemaic dynastic cult together as the Theoi Philopatores kai Philadelphoi (Father-loving and Sibling-loving Gods). This title was probably meant to reinforce Ptolemy XII's claim to the throne in the face of claims that his parentage meant that he was an illegitimate son of Ptolemy IX and therefore not entitled to rule.[30]

In 76 BC, the High Priest of Ptah in Memphis died and Ptolemy XII travelled to Memphis to appoint his fourteen-year-old son, Pasherienptah III, as the new High Priest. In turn, Pasherienptah III crowned Ptolemy as Pharaoh and then went to Alexandria, where he was appointed as Ptolemy XII's 'prophet'. These encounters are described in detail on Pasherienptah's funerary stela, Stele BM 866, and they demonstrate the extremely close and mutually reinforcing relationship that had developed between the Ptolemaic kings and the Memphite priesthood by this date.[30]

In August 69 BC, Cleopatra V ceases to be mentioned as co-regent. The images of her that had been carved on the main pylon of the Temple of Horus at Edfu were covered over at this time. The reason for this sudden shift is unknown, but presumably she was divorced at this time.[30] Ptolemy adopted a new royal epithet Neos Dionysos (New Dionysus) at some time after this; Chris Bennett proposes that the epithet was linked to the break with Cleopatra.[22]

Relations with Rome

[edit]

When Ptolemy X had died in 88 BC, his will had left Egypt to Rome in the event that he had no surviving heirs. Although the Romans had not acted on this, the possibility that they might forced the following Ptolemies to adopt a careful and respectful policy towards Rome.[33][34] Ptolemy XII continued this pro-Roman policy in order to protect himself and secure his dynasty's fate. Egypt came under increasing Roman pressure nevertheless. In 65 BC, the Roman censor, Marcus Licinius Crassus proposed that Rome annex Egypt.[35] This proposal failed in the face of opposition from Quintus Lutatius Catulus and Cicero. In light of this crisis, however, Ptolemy XII began to expend significant resources on bribing Roman politicians to support his interests. In 63 BC, when Pompey was reorganising Syria and Anatolia following his victory in the Third Mithridatic War, Ptolemy sought to form a relationship with Pompey by sending him a golden crown. Ptolemy also provided pay and maintenance for 8,000 cavalry to Pompey for his war with Judaea. He also asked Pompey to come to Alexandria and help to put down a revolt which had apparently broken out in Egypt; Pompey refused.[36][33][37]

The money required for these bribes was enormous. Initially, Ptolemy XII funded them by raising taxes. A strike by farmers of royal land in Herakleopolis which is attested in a papyrus document from 61/60 BC has been interpreted as a sign of widespread discontent with this taxation. Increasingly, Ptolemy XII also had recourse to loans from Roman bankers, such as Gaius Rabirius Postumus. This gave the Romans even more leverage over his regime and meant that the fate of Egypt became an increasingly immediate issue in Roman politics.[33]

Finally, in 60 BC, Ptolemy XII travelled to Rome, where the First Triumvirate, composed of Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar, had just taken power, in order to negotiate official recognition of his kingship. Ptolemy paid Pompey and Caesar six thousand talents – an enormous sum, equivalent to the total annual revenue of Egypt.[38] In return, a formal alliance or foedus was formed. The Roman Senate recognised Ptolemy as king and Caesar passed a law that added Ptolemy to the list of friends and allies of the people of Rome (amici et socii populi Romani) in 59 BC.[39][40][41]

In 58 BC, the Romans took control of Cyprus, causing its ruler, Ptolemy XII's brother, to commit suicide.[42] Ptolemy XII took no action in response to his brother's death and Cyprus remained a Roman province until returned to Ptolemaic control by Julius Caesar in 48 BC.[43]

Exile in Rome (58–55 BC)

[edit]The bribery policy had been unpopular in Egypt for a long time, both because of its obsequiousness and because of the heavy tax burden that it entailed, but the annexation of Cyprus demonstrated its failure and enraged the people of Alexandria. The courtiers in Alexandria forced Ptolemy to step down from the throne and leave Egypt.[44] He was replaced by his daughter Berenice IV, who ruled jointly with Cleopatra Tryphaena (known to modern historians as Cleopatra VI), who was probably Ptolemy XII's former wife but may be an otherwise unattested daughter. Following Cleopatra Tryphaena's death a year later, Berenice ruled alone from 57 to 56 BC.[45][43]

Probably taking his daughter Cleopatra VII with him, Ptolemy fled for the safety of Rome.[46][47][48][49] On the way, he stopped in Rhodes where the exiled Cato the Younger offered him advice on how to approach the Roman aristocracy, but no tangible support. In Rome, Ptolemy XII prosecuted his restitution but met opposition from certain members of the Senate. His old ally Pompey housed the exiled king and his daughter and argued on behalf of Ptolemy's restoration in the Senate.[50][43] During this time, Roman creditors realized that they would not get the return on their loans to the king without his restoration.[51] In 57 BC, pressure from the Roman public forced the Senate's decision to restore Ptolemy. However, Rome did not wish to invade Egypt to restore the king, since the Sibylline books stated that if an Egyptian king asked for help and Rome proceeded with military intervention, great dangers and difficulties would occur.[52]

Egyptians heard rumours of Rome's possible intervention and disliked the idea of their exiled king's return. The Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote that a group of one hundred men were sent as envoys from Egypt to make their case to the Romans against Ptolemy XII's restoration. Ptolemy seemingly had their leader Dio of Alexandria poisoned and most of the other protesters killed before they reached Rome.[53]

Restoration and second reign (55–51 BC)

[edit]

In 55 BC, Ptolemy paid Aulus Gabinius 10,000 talents to invade Egypt and so recovered his throne. Gabinius defeated the Egyptian frontier forces, marched to Alexandria, and attacked the palace, where the palace guards surrendered without fighting.[55] The exact date of Ptolemy XII's restoration is unknown; the earliest possible date of restoration was 4 January 55 BC and the latest possible date was 24 June the same year. Upon regaining power, Ptolemy acted against Berenice, and along with her supporters, she was executed. Ptolemy XII maintained his grip on power in Alexandria with the assistance of around two thousand Roman soldiers and mercenaries, known as the Gabiniani. This arrangement enabled Rome to exert power over Ptolemy, who ruled until he fell ill in 51 BC.[56] On 31 May 52 BC his daughter Cleopatra VII was named as his coregent.[57]

At the moment of Ptolemy XII's restoration, Roman creditors demanded the repayment of their loans, but the Alexandrian treasury could not repay the king's debt. Learning from previous mistakes, Ptolemy XII shifted popular resentment of tax increases from himself to a Roman, his main creditor Gaius Rabirius Postumus, whom he appointed dioiketes (minister of finance), and so in charge of debt repayment. Perhaps Gabinius had also put pressure on Ptolemy XII to appoint Rabirius, who now had direct access to the financial resources of Egypt but exploited the land too much. The king had to imprison Rabirius to protect his life from the angry people, then allowed him to escape. Rabirius immediately left Egypt and went back to Rome at the end of 54 BC. There he was accused de repetundis, but defended by Cicero and probably acquitted.[58][59] Ptolemy also permitted a debasing of the coinage as an attempt to repay the loans. Near the end of Ptolemy's reign, the value of Egyptian coinage dropped to about fifty per cent of its value at the beginning of his first reign.[60]

Ptolemy XII died sometime before 22 March 51 BC.[61] His will stipulated that Cleopatra VII and her brother Ptolemy XIII should rule Egypt together. To safeguard his interests, he made the people of Rome executors of his will. Since the Senate was busy with its own affairs, his ally Pompey approved the will.[62]

Legacy and assessments

[edit]Generally, descriptions of Ptolemy XII portray him as weak and self-indulgent, drunk, or a lover of music.[65] According to Strabo, his practice of playing the flute earned him the ridiculing sobriquet Auletes ('flute player'):

Now all of the kings after the third Ptolemy, being corrupted by luxurious living, administered the affairs of government badly, but worst of all were the fourth, seventh, and the last, Auletes, who, apart from his general licentiousness, practised the accompaniment of choruses with the flute, and upon this he prided himself so much that he would not hesitate to celebrate contests in the royal palace, and at these contests would come forward to vie with the opposing contestants.

— Strabo, XVII, 1, 11, [66]

According to the author Mary Siani-Davies:

Throughout his long-lasting reign the principal aim of Ptolemy was to secure his hold on the Egyptian throne so as to eventually pass it to his heirs. To achieve this goal he was prepared to sacrifice much: the loss of rich Ptolemaic lands, most of his wealth and even, according to Cicero, the very dignity on which the mystique of kingship rested when he appeared before the Roman people as a mere supplicant.

— Mary Siani-Davies, "Ptolemy XII Auletes and the Romans", Historia (1997) [62]

Marriage and issue

[edit]Ptolemy married his sister Cleopatra V, who was with certainty the mother of his eldest known child, Berenice IV.[67] Cleopatra V disappears from court records a few months after the birth of Ptolemy XII's second known child,[68] and probably hers, Cleopatra VII in 69 BC.[69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76] The identity of the mother of the last three of Ptolemy XII's children, in birth order Arsinoe IV, Ptolemy XIII, and Ptolemy XIV, is also uncertain. One hypothesis contends that possibly they (and perhaps Cleopatra VII) were Ptolemy XII's children with a theoretical half Macedonian Greek, half Egyptian woman belonging to a priestly family from Memphis in northern Egypt,[68] but this is only speculation.[77]

The philosopher Porphyry (c. 234 – c. 305 AD) wrote of Ptolemy XII's daughter Cleopatra VI, who reigned alongside her sister Berenice IV.[78] The Greek historian Strabo (c. 63 BC – c. AD 24) stated that the king had only three daughters of whom the eldest has been referred to as Berenice IV.[79] This suggests that the Cleopatra Tryphaena mentioned by Porphyry may not have been Ptolemy XII's daughter, but his wife. Many experts now identify Cleopatra VI with Cleopatra V.[67]

| Name | Image | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berenice IV | 79-75 BC | early 55 BC | Queen of Egypt (June 58 BC – early 55 BC)[80] | |

| Cleopatra VII |  |

December 70 BC or January 69 BC | 12 August 30 BC | Queen of Egypt (51 - 30 BC)[81] |

| Arsinoe IV | 63-61 BC? | 41 BC | Queen of Cyprus in 48 BC, claimed queenship of Egypt from late 48 BC until expelled by Julius Caesar in early 47 BC[82] | |

| Ptolemy XIII | 62-61 BC | 13 January 47 BC | Co-regent with Cleopatra VII (51 – 47 BC)[83] | |

| Ptolemy XIV |  |

60-59 BC | June–September 44 BC | Co-regent with Cleopatra VII (47 – 44 BC)[84] |

References

[edit]- ^ "Ptolemy XII Auletes | Macedonian king of Egypt | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Ptolemaic Dynasty -- Ptolemy XII root". instonebrewer.com. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Cicero Agr. 2.42; Pausanias 1.9.3

- ^ Sullivan 1990, p. 92.

- ^ Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- ^ Ernle Bradford, Classic Biography: Cleopatra (Toronto: The Penguin Groups, 2000), p. 28.

- ^ Lefkowitz (1997), pp. 44–45, 50.

- ^ Schiff (2010), pp. 24.

- ^ Watterson (2020), pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Hölbl 2001, p. 222.

- ^ Huß 2001, p. 203.

- ^ Cheshire 2011, pp. 20–30.

- ^ Lippert 2013, pp. 33–48.

- ^ a b Bennett 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2011, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Stanwick 2010, p. 60.

- ^ Salisbury, Joyce E., Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World (2001), p.50: "Cleopatra IV had money and spirit enough to challenge this move, so she went to Cyprus...Cleopatra IV went with her army to Syria and offered her services to her cousin Antiochus Cyzicenus...Cleopatra IV married Cyzicenus to strengthen his ability to rule."

- ^ Lightman, Marjorie, and Lightman, Benjamin, A to Z of Ancient Greek and Roman Women (2008), p.80: "In Antioch, Cleopatra offered her support to Cyzicenus and married him. Grypus captured Antioch and Cleopatra in 112 B.C.E. ...her sister, fearing Cleopatra would seduce her husband, had Cleopatra killed"

- ^ Penrose, Walter Duval, Postcolonial Amazons: Female Masculinity and Courage in Ancient Greek and Sanskrit Literature (2016), p.218: "Having been expelled from the throne, Cleopatra IV now went to Cyprus, where she gathered an army. She may have originally hoped to use this force to march on Egypt in protest of her mother's action...instead she offered to marry the Seleucid contender for the throne, Antiochus IX Cyzicenus, and, using her mercenary army to help his cause, set off to become queen of Syria (Just. 39.3.3)...Grypus took Antioch in 112 BCE and [her sister] Tryphaena, Grypus' wife and Cleopatra's IV's own sister, ordered the death of Cleopatra IV (Just. 39.3.4-11)."

- ^ a b Hölbl 2001, p. 206-207.

- ^ SEG IX.5.

- ^ a b c Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy IX". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Justin Epitome of the Philippic History 39.4

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 13.13.1

- ^ Whitehorne 1994, p. 139.

- ^ Hölbl 2001, p. 211-213.

- ^ Appian, Mithridatica 16.111

- ^ Bradford 2000, p. 33.

- ^ Roller 2010, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Hölbl 2001, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Bennett 1997, p. 39.

- ^ "Portrait féminin (mère de Cléopâtre ?)" (in French). Musée Saint-Raymond. Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Hölbl 2001, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Siani-Davies 1997, p. 307.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Crassus 13.2

- ^ Appian, Mithridatica 114; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 14.35

- ^ Bradford 2000, p. 35.

- ^ Suetonius Life of Julius Caesar 54.3

- ^ Caesar Bellum Civile 3.107; Cicero, Pro Rabirio Postumo 3; Cicero, Letter to Atticus 2.16.2

- ^ Siani-Davies 1997, p. 316.

- ^ Hölbl 2001, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Roller 2010, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Hölbl 2001, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Cassius Dio 39.12; Plutarch, Life of Pompey 49.7.

- ^ Siani-Davies 1997, p. 324.

- ^ Bradford 2000, p. 37.

- ^ Roller, Duane W. (2010), Cleopatra: a biography, p.22, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-536553-5.

- ^ Fletcher, Joann (2008), Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend, p.76, New York: Harper, ISBN 978-0-06-058558-7

- ^ Joann Fletcher expresses little doubt that Cleopatra VII accompanied her father, noting an ancient Greek primary source stating that Ptolemy XII traveled with one of his daughters; since Berenice IV was his ruling rival and Arsinoe IV was a toddler, Fletcher believes it must have been Cleopatra (who was later made his regent and named his successor in his will). cf Fletcher, Joann (2008), Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend, pp=76–77, 80, 84–85, New York: Harper, ISBN 978-0-06-058558-7

- ^ Strabo Geography 17.1.11; Cassius Dio 39.14.3

- ^ Siani-Davies 1997, p. 323.

- ^ Bradford 2000, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Siani-Davies 1997, p. 325.

- ^ Svoronos 1904, vol. I-II, p=302 (n°1838), & vol. III-IV, plate LXI, n°22, 23..

- ^ Bradford 2000, p. 43.

- ^ Siani-Davies 1997, p. 338.

- ^ Roller 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Cicero.

- ^ Huß 2001, pp. 696–697.

- ^ Siani-Davies 1997, pp. 332–334.

- ^ Roller 2010, pp. 53, 56.

- ^ a b Siani-Davies 1997, p. 339.

- ^ a b Bard, Kathryn A., ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-134-66525-9.

- ^ a b mondial, UNESCO Centre du patrimoine. "Pharaonic temples in Upper Egypt from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". UNESCO Centre du patrimoine mondial (in French).

- ^ Bradford 2000, p. 34.

- ^ Strabo XVII, 1, 11.

- ^ a b Tyldesley 2006, p. 200.

- ^ a b Roller 2010, pp. 16, 19, 159.

- ^ Grant 1972, p. 4.

- ^ Preston 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Jones 2006, p. xiii.

- ^ Schiff 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Kleiner 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Tyldesley 2006, pp. 30, 235–236.

- ^ Meadows 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Bennett 1997, p. 60-63.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2011, pp. 127, 128.

- ^ "Eusebius: Chronicle p. 167, accessed online". Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ Strabo, Geography, Book XVII, pp. 45–47, accessed online

- ^ Bennett, Chris. "Berenice IV". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ Bennett, Chris. "Cleopatra VII". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ Bennett, Chris. "Arsinoe IV". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy XIII". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy XIV". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Southern (2009, p. 43) writes about Ptolemy I Soter: "The Ptolemaic dynasty, of which Cleopatra was the last representative, was founded at the end of the fourth century BC. The Ptolemies were not of Egyptian extraction, but stemmed from Ptolemy Soter, a Macedonian Greek in the entourage of Alexander the Great."For additional sources that describe the Ptolemaic dynasty as "Macedonian Greek", please see Roller (2010, pp. 15–16), Jones (2006, pp. xiii, 3, 279), Kleiner (2005, pp. 9, 19, 106, 183), Jeffreys (1999, p. 488) and Johnson (1999, p. 69). Alternatively, Grant (1972, p. 3) describes them as a "Macedonian, Greek-speaking" dynasty. Other sources such as Burstein (2004, p. 64) and Pfrommer & Towne-Markus (2001, p. 9) describe the Ptolemies as "Greco-Macedonian", or rather Macedonians who possessed a Greek culture, as in Pfrommer & Towne-Markus (2001, pp. 9–11, 20).

- ^ Lefkowitz (1997) rejects the notion of an Egyptian mother for Ptolemy XII, with some writers speculating that would be why Cleopatra spoke Egyptian. Lefkowitz notes, however, that if Cleopatra's paternal grandmother had been Egyptian, it would have been more likely Ptolemy XII was the first speaker of the Egyptian language, instead of his daughter Cleopatra.

Primary sources

[edit]- Cassius Dio, Roman history 39.12 – 39.14, 39.55 – 39.58

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (2018) [54 BC]. pro Rabirio Postumo [In Defense of Gaius Rabirius Postumus]. Latin Texts & Translations. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- Strabo, Geographica 12.3.34 and 17.1.11

Secondary sources

[edit]- Bennett, Christopher J. (1997). "Cleopatra V Tryphæna and the Genealogy of the Later Ptolemies". Ancient Society. 28: 39–66. doi:10.2143/AS.28.0.630068. ISSN 0066-1619. JSTOR 44079777. (registration required)

- Bradford, Ernle Dusgate Selby (2000). Cleopatra. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0141390147. (registration required)

- Cheshire, Wendy (2011), "The Phantom Sister of Ptolemy Alexander", Enchoria, 32: 120–130.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith (2011). Antony and Cleopatra. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-300-16534-0.

- Grant, Michael (1972). Cleopatra. Edison, NJ: Barnes and Noble Books. ISBN 978-0880297257.

- Hölbl, Günther (2001). A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. London & New York: Routledge. pp. 222–230. ISBN 0415201454.

- Huß, Werner (2001). "Ägypten in hellenistischer Zeit 332–30 v. Chr. (Egypt in Hellenistic times 332–30 BC)". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. Munich. ISSN 0307-5133. (in German)

- Jones, Prudence J. (2006). Cleopatra: a sourcebook. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806137414.

- Kleiner, Diana E. E. (2005). Cleopatra and Rome. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674019058. (registration required)

- Lefkowitz, Mary R. (1997). Not out of Africa: How Afrocentrism became an Excuse to Teach Myth as History. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-09838-5. (registration required)

- Lippert, Sandra (2013), "What's New in Demotic Studies? An Overview of the Publications 2010-2013" (PDF), The Journal of Juristic Papyrology: 33–48.

- Mahaffy, John Pentland (1899). A History of Egypt under the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Vol. IV. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Meadows, Andrew (2001), "Sins of the fathers; the inheritance of Cleopatra, last queen of Egypt", in Walker, Susan; Higgs, Peter (eds.), Cleopatra of Egypt: from History to Myth, Princeton, NJ: British Museum Press), pp. 14–31, ISBN 978-0714119434

- Preston, Diana (2009). Cleopatra and Antony. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0802710598.

- Roller, Duane W. (2010). Cleopatra: a Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-36553-5. (registration required)

- Schiff, Stacy (2010). Cleopatra: A Life. New York: Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-12180-4.

- Siani-Davies, Mary (1997). "Ptolemy XII Auletes and the Romans". Historia. 46 (3): 306–340. JSTOR 4436474. (registration required)

- Stanwick, Paul Edmund (2010). Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek Kings as Egyptian Pharaohs. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292777729.

- Svoronos, Ioannis (1904). Ta nomismata tou kratous ton Ptolemaion. Vol. 1 & 2, and 3 & 4. Athens. OCLC 54869298.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (in Greek and German)

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2006). Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500051450.

- Watterson, Barbara (2020). Cleopatra: Fact and Fiction. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-445-66965-6.

- Whitehorne, John (1994). Cleopatras. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05806-3.

External links

[edit]- Ptolemy XII by Christopher Bennett (part of his Egyptian Royal Genealogy)

- Ptolemy XII Auletes from the online Encyclopædia Britannica

- Strabo The Geography in English translation, ed. H. L. Jones (1924), at LacusCurtius (Bill Thayer's Web Site)

- Cassius Dio Roman History in English translation by Cary (1914–1927), at LacusCurtius (Bill Thayer's Web Site)

- The House of Ptolemy, Chapter XII by E. R. Bevan (Bill Thayer's Web Site)

- Ptolemy XII Auletes (ca. 112 - 51 BCE) entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

Lua error in Module:Navbox_with_collapsible_groups at line 6: attempt to call field 'with collapsible groups' (a nil value).